How Cell Phones Work

Now an absolutely indispensable tool in the modern 21st century world, cellular phones started becoming popular in the mid 1980s.

How does it all work? -- The phones, towers, radio signals, etc. We'll discuss all that below.

But first (yeah, you knew it was coming) a little history on mobile phones.

The first commercially available car phone arrived in the mid 1940s(!) in St. Louis. By the mid 1960's there were upward 50,000 private car phones. The handset and cradle mounted under the dashboard looked a bit like a dial telephone but the real guts were in a massive suitcase-sized cabinet in the trunk of the car.

Cellular antenna tower with graphical illustration

Car phone in the mid 60s

These pre-cellular mobile phones were expensive to buy and use. And since they were so massive they had to be installed and wired into the car. You'd also have a good-sized antenna on the car, usually mounted to the trunk lid. No bringing this thing into a bar.

There was no "cellular" (more on that below) in these early mobile phones so a given radio frequency could be used by only one user at a time for an entire city. And since there were only a handful of channels, then only a couple of dozen or so people could be using the network at the same time. Imagine that.

The transmitters were quite powerful in order for the phone to work all over a city. And once you drove away from the city then your phone would no longer work.

No calling "plans", either. You paid by the minute and it wasn't cheap.

Suffice to say, most regular people didn't own one of these. This was Rockefeller-level territory due to cost and being able to bypass lengthy waiting lists.

Mobile phones for mere mortals started becoming available in the mid 1980s with the advent of cellular technology. These weren't cheap, either. But at least they were somewhat affordable and, most importantly, the new cellular topology allowed for thousands of simultaneous users. Costs quickly came down.

The Magic of Cellular

Instead of a single mobile user hogging-up an entire radio frequency (channel) for an entire city, what if it was possible to simultaneously reuse that same channel many times over in the same city?

That's what cellular technology can do.

What made cellular so practical (and efficient) was simultaneous use of radio frequencies across a city. It's called "cellular" because each tower covered a "cell" which could be as small as a quarter mile radius on up to several miles radius depending on population and use density in that particular cell.

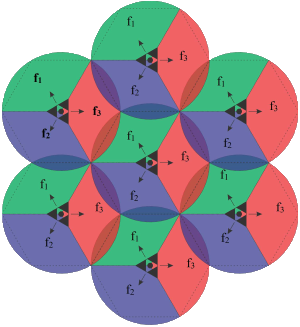

Most cell towers have three sets of directional antenna that each covers a 120 degree (1/3rd of a circle) field. Each antenna grouping is capable of transmitting and receiving on hundreds of channels simultaneously. The three colors shown on the graphic illustrate how tightly a channel can be reused without interference. By splitting into thirds like this, reuse can be tighter, increasing capacity.

Illustration of how channels can be reused

Today, most people are communicating via non-voice means -- text messages, email, using apps, etc. These non-realtime protocols are far less sensitive to latency (delays) than voice-calls so that means precious channels aren't locked up nearly as much which, in turn, yields even more simultaneous use capability.

Today, all cellular signaling is digital rather than analog. Digital signaling, combined with advanced multiple access techniques, significantly increases channel efficiency, enabling thousands of users to connect simultaneously within a single cell.

Cruisin' Down the Highway

Cellular topology has many advantages. We discussed a major advantage just above -- being able to reuse precious and limited channels many times within a city or region. But since the cells are not very big, then what happens if you drive outside of the range of your cell?

That's where the magic of cellular hand-off comes in.

Your mobile device is always looking for the best quality signal. When you're on the move, especially in more or less the same direction like being on a highway, then at some point your phone will have to switch from one tower to another. That's called "hand-off" and it's transparent to you. In the old analog days of cellular back in the 80s, you could tell when you switched towers because you'd hear a brief electronic-sounding "tzzzt". Then your call would continue. Today it's all digital and you do not notice when a hand-off takes place.

Another advantage to cellular topology is not needing a lot of power. Smartphones have pretty small batteries so its important to keep transmitting power as low as possible. By having a nearby tower then your phone can talk to it using very little power. Not like it was back in the 1960s when your big, heavy, power hungry car phone needed to transmit 25 miles or more.

Nowhere to Hide

One of the (some would say unfortunate) side effects of cellular technology is the ability for the cell phone providers (Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile, etc.) to pretty accurately determine where you are without necessarily relying on GPS location data. Although you can deny location permission to apps on your phone, you cannot deny location to the cellular radio itself.

Knowing where your mobile phone is (within a short range -- maybe a few hundred feet or so?) is important to making the cellular network operate. Even cheap pre-GPS flip phones can be tracked in this way. Although most phones today, even flip phones, have GPS chips.

So how does that work? How could a phone without GPS be located?

Via triangulation and/or trilateration, that's how. Even though your phone might only be connected to the nearest/strongest tower, it's still pinging (saying "hello") several nearby towers. It has to, in fact, so it can know which tower is providing the best signal and when it's time to hand-off.

The network can determine your phone's location by measuring the time of flight (trilateration) and/or the angle of arrival (triangulation) of the radio signals between your phone and the various nearby cell towers. By using triangulation/trilateration and working through some mathematical formulas, the network can figure out where your device is with decent accuracy. Maybe not pinpoint accuracy, but often within a short walk, especially in non-rural settings.

So because of this, there is no anonymity to your location. The GPS chips just makes it even more accurate, within mere feet. Denying location data might keep TikTok from knowing where you are in that moment but the cellular network always knows where you are if you're carrying a phone and it's powered on.

And you don't have to be a bad guy for this to be a potential problem.

Location data, especially realtime, is incredibly valuable and "big data" wants to scoop up as much location data on you as possible. Worse, data brokers aren't overly picky about who they do business with, either. For a couple of hundred bucks or knowing the right people (not easy, but not all that hard, either) you can get location data on pretty much anyone you want -- possibly even real time data.

Renting a car and you drove where you weren't supposed to go? Perhaps over certain international borders? Say hello to a steep surcharge or loss of insurance coverage!

In today's political climate, even being tracked to certain locations (e.g. family planning clinics) could be troublesome. A women needing reproductive healthcare and living in certain states would do well to leave her phone at home.

The Long Island Long Arm of the Law

One of (several) key investigative techniques that led to identifying a prime suspect in the Gilgo Beach murders was tracking cell phone use. The perpetrator was careful to use anonymous prepaid burner phones, likely bought with cash, that could not be tied to him. Perhaps he chose cheap flip-phones that have no GPS capability. (This is speculation on my part, but it's possible.)

Recall that I mentioned that a cellular network can reasonably-accurately locate a phone via triangulation. Maybe not to an exact street address but close enough to make other investigative techniques practical. The perp apparently contacted his victims, using a fresh burner phone for each of them, primarily from two locations -- near his home on Long Island and near his office in Manhattan.

It was easy enough to tie the burner phones to each victim's phone number. After all, the perp used the phones to call his victims to arrange his meetings with them. That's all in the calling logs kept by the phone companies. But how did investigators tie the phones to the perp? Prepaid phones bought with cash require no identification in the US.

The investigators got tower dumps (records of phones and when they were connected to said tower) and found patterns in the data. It's possible that the tower dump data contained sufficient timing information that could allow for triangulating the device's location. Sophisticated software can then draw a polygon around where that burner phone would have been when the calls were made. Still not as accurate as true GPS coordinates (which can be accurate to within a few feet) but likely apparently enough to provide key input to allow other investigative techniques (such as DNA matching, etc.) to proceed that ultimately led to his identification.

But were it not for the call data downloaded from the towers and analyzed, it's possible the perp would not have been found. Sophisticated tools, combined with a good measure of old fashioned (in the good sense) gumshoe police work ultimately broke this case.